Due to the fact I have previously studied a little of the japanese language in the past, I was aware of some of the more commonly used kanji characters having directly pictorial origins, and with the use of this very useful children's learning website: http://web-japan.org/kidsweb/language/quickkanji/index.html I was able to illustrate some of the most obvious abstractions.

While you would not immediately think "fire" or "sun" if you viewed these symbols independently, the meaning becomes clear when the progression of abstraction, or continuum, is also provided.

I find the symbol for "tree" especially interesting, because while it is one of the most obvious symbols, it can be seen in more than one way: some see the horizontal line representing the earth, with the tree above the ground and the three "roots" below the earth, while others see the entire symbol as the tree with the horizontal line representing the upper branches, and the sweeping lines below it representing the lower limbs. It is also quite satisfying that the symbols for "woods" or "forest" are simply the tree symbol multiplied, which is very easily understood by anyone learning the language.

The kanji for rice paddy is rather obvious; the one for fish is not. That gives me the idea that the kanji for fish actually is the simplified version of a sketch someone made of a fish, due to the fact that fishes differ in appearance.

While Kanji is based on pictographs, there is a lot more to this writing system, such as the combination of characters to derive a different meaning. There are a few ways of doing this.

Simple Ideographs

These are symbols that are used to represent directions and ideas that do not have a direct image to derive from.

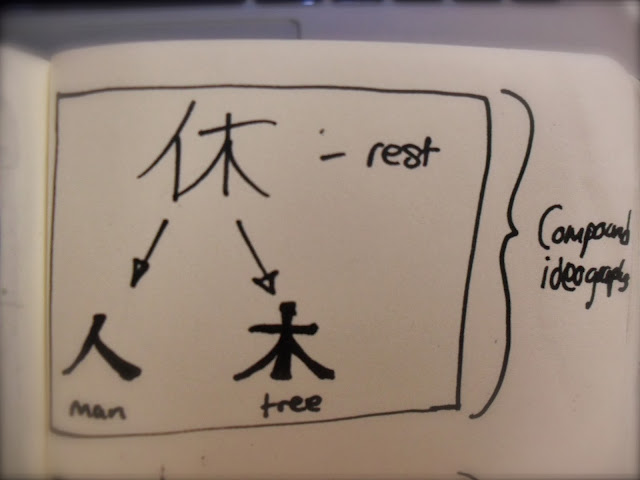

Compound Ideographs

The characters for "woods" and "forest" are compound ideographs- more than one symbol placed together to form another character. There are countless combinations with many different meanings.

The above example is the Kanji for rest, which is the combination of the character for "man" and the character for "tree" representing a person leaning against a tree, therefore taking a rest. From what I have seen, the origins of compound ideographs are pretty logical like this.

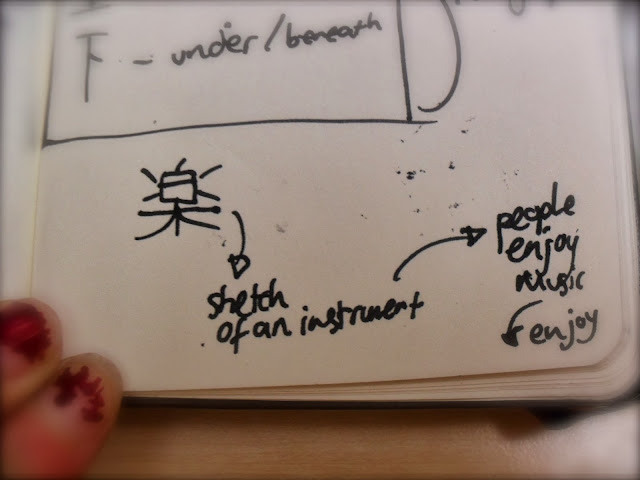

Derivative Characters

These are more indications than actual symbols; more like characters that relate to an idea rather than directly represent it.

The above character means "to enjoy" however, because there isn't a pictorial representation of that, we have here in stead an abstracted version of a sketch of a musical instrument, and because people enjoy music, this symbol therefore can be derived to mean "enjoy.

I personally find Kanji fascinating, as not only are there hundreds and thousands of characters with different symbolic qualities, but even more combinations of characters to be learned.